Merging Facebook data with administrative records is amazing for social self-understanding ... we need more of this sort of work, while avoiding creepy surveillance

My colleagues' work provides a glimpse of what it could be for society to understand itself better … but to really unlock this power for good without creepy surveillance requires data unions

My colleagues at the Behavioural Insights Team published a remarkable study of UK social mobility and social capital last week. They combined the already astounding richness of the administrative Longitudinal Educational Outcomes (LEO) database with Facebook records of 20 million 25-64 year-old UK residents and with further Office for National Statistics survey data on life satisfaction. There are many remarkable things about this study. One, from the perspective of the intricacies of social research, is simply the feat of having matched, at a national scale, individual records over time across education, employment, income, the Facebook friendship graph and subjective wellbeing. This offers a glimpse into how, as a society, we can really come to understand ourselves better.

The good that could one day come out of such generalised social understanding is immense. Take, for example, the really very high quality conversation between Rachel Reeves and Nick Robinson earlier this week in which the Chancellor defended her approach to welfare cuts (all very calmly and cogent, in my view … worth listening to the clip … what a difference it makes, I felt, having intelligent people in charge whose goodwill you don’t have to always be questioning…). [And another aside, if I may - does the BBC site allow you to share and link to a specific point in a programme? I couldn’t see it, and had to go through what feels like the very Web1.0 kludge of re-recording the audio and uploading to somewhere accessible…].

A very big part of Reeves’ defence of her cuts was the following: the welfare system currently creates perverse incentives and is poorly targeted; with higher minimum wages and better help getting people back to work, it ought to be possible to do all of the following at once: increase welfare payments to the most needy; increase the income of those who reduce their welfare receipts by working more; increase their life-satisfaction (because work does, in most cases, even for those with disabilities, enhance wellbeing); reduce overall government spending on welfare; increase overall government receipts from employment and VAT. What’s not to like?

It is an attractive pitch. Coming back to questions of data, note that it rests crucially on better targeting of welfare programmes, making sure that back-to-work practices at Job Centres are more effective. Now imagine the kind of work that my BIT colleagues did, but with even more information: let’s look at the subset of those in the dataset who have been on Personal Independence Payment … can we identify any groups that seem to do unexpectedly well in terms of getting back to work? … what else do they have in common? … perhaps their Job Centres have all followed a set of practices that are not followed everywhere? … or maybe it is not the Job Centre but some other more unexpected aspect of social interaction … can we look at what their diets have been? … their NHS interactions? … their levels of debt? … their participation in collective social activities? There is so much to explore, and so much that a society that understands itself better might do.

One of the intriguing aspects of the BIT/META et al results is that if you have more cross-class friendships, your social mobility is higher. This is very nicely written up by my colleague Ravi Gurumurthy on his policy substack. As he says, “While the research does not establish causality, it does suggest that if we can foster cross-class friendships, it will increase social mobility, trust and wellbeing. This form of social capital therefore deserves far more attention than the occasional ministerial speech on the importance of building communities.”

When I read this, my thoughts immediately turned to a project I am closely involved in, the Meanwhile Gardens Community Association. We are a small charity in North Kensington that looks after a community garden, a playhut for under-fives, a skatebowl, and we have a close association with the Metronomes Steel Orchestra. As I say on every funding application we send out: “Meanwhile Gardens is a beautiful and much-loved 4-acre community garden in North Kensington. It is a part of London marked by stark inequalities: our ward is ranked amongst the poorest nationally despite being a stone’s throw from some of the wealthiest.” We are one of those “big tents” in which a great deal of social mixing occurs. The playhut is patronised both by parents living in the neighbouring council estates and by nannies looking after children in the millionaires’ houses down the road; the skatebowl, London’s first free-to-use bowl, and still free to use, has thrill-seeking children from all socio-economic groups, where status is measured according to a very different (and, imo, healthy) hierarchy of skill; the gardens themselves are tended by volunteers - middle-class gardening enthusiasts, people recovering from mental ill-health, and many seeking company and a sense of collective purpose and achievement.

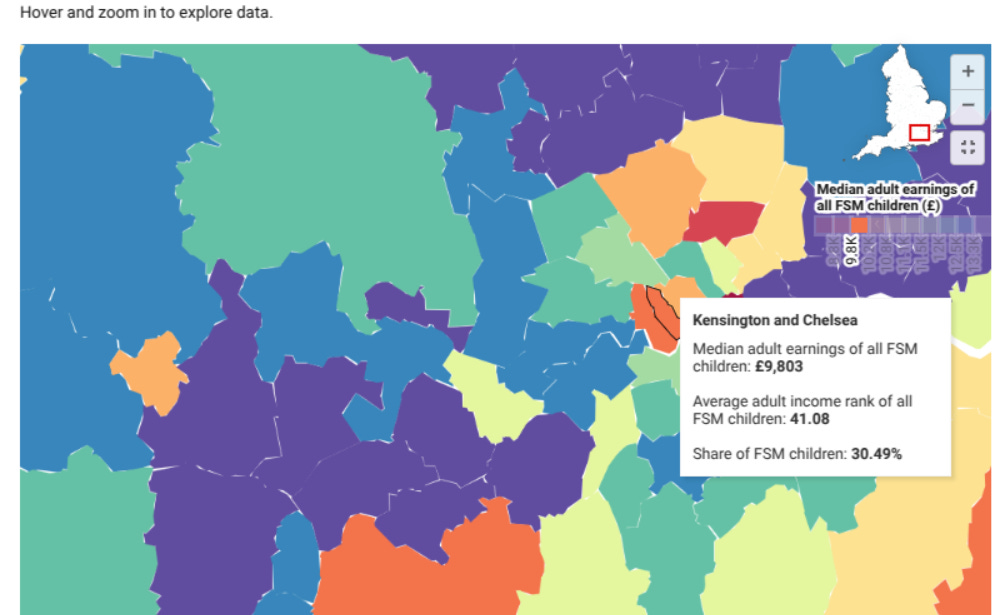

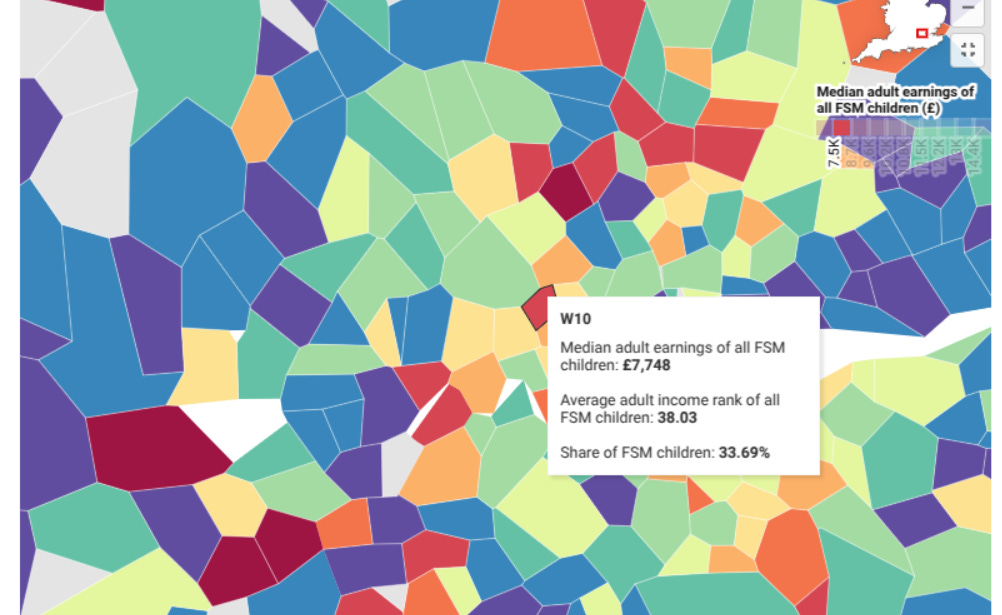

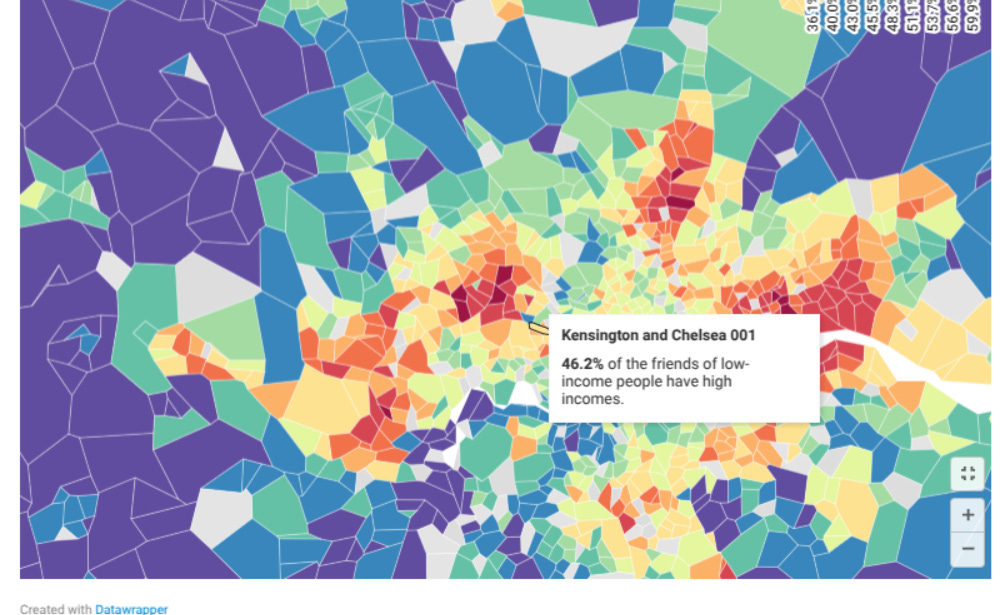

You can probably tell that I think that the gardens do a lot of good locally. But I wish I could offer funders some really solid evidence of the difference that we make. The BIT/META work offers some tantalising hints. After all, social mixing is meant to be correlated with social mobility … so can we see any of that around the gardens? The first screenshot shows the data at the level of local authorities, zoomed in to Kensington and Chelsea: 30% of children in the borough are eligible for Free School Meals (it is a very rich borough in the middle and southern parts). The dataset allows zooming into more granular areas. So in the next screenshot, I zoom in on the area that the gardens sit in to get the measure of social mobility. The adult earnings of adults whose children qualify for Free School Meals is down almost one quarter and the share of FSM children up 3%. That all goes in the direction I know well, but it is still not granular enough. The third screengrab shows the various measures of social capital for areas at an even more granular level than the second. The patch with the gardens shows 46.2% of friends of low income people have high incomes. The patch just to teh south of the gardens scores less well, at 44.5%.

All very intriguing. But clearly not the slam-dunk I need to send to funders - or, indeed, need to change our programmes in the gardens. So … with a data hat on, what would actually help?

Imagine a future in which we could do the following?

Ask all families coming to the playhut (who have to register anyway) whether they’d allow us to work with their data union (/club/trust/fiduciary) to evaluate our impact; do the same with the skateboarders and the members of the Metronomes

For those that agreed, we would push their playhut attendance to their data vault at their union

We would ask the union,, where the members had expressed consent for such things, to make available the data to social researchers doing programme evaluations

Researchers, doing even richer versions of the kind of work described above, could include participation in our programmes as an explanatory variable to their models

… and who knows … one day we might get an email from someone with relevant findings for us, perhaps something about best practice, things we could try, or even being told that we seem to be having the kind of effect that we all hope we’re having.

You can see where I am going with all this. It is amazing that Meta has made this data available for research. Well done. But what is not amazing is that it is only Meta data, and that even the Meta data came in a form available for research because of the (occasional) beneficence of Meta rather than as of right to the data subjects.

Society needs to understand itself better. Progress of all sorts will come from that. To do that properly, we need to create an environment in which large pools of consented data are routinely collected and made available for good uses. The BIT work is just a glimpse of that future … enrolling citizens into data unions is a necessary step to unlocking it.